Absract

The term “preventive detention” refers to the state’s practice of imprisoning people without trial because it believes they will commit a crime in the future. Despite appearing to contradict the concepts of natural justice andindividual liberty,the Indian Constitution provides legal support in some cases. This article examines the history, legal framework, statutory provisions, court

rulings, and current issues involving preventive detention in India. It examines the delicate balance between individual liberties and state security by tracking the evolution of colonial precedents to current laws such as the National Security Act of 1980.

Introduction

The state may detain if it believes they may commit an offense in the future. Preventive detention is anticipatory in nature, as opposed to punitive detention, which is applied after an offense has been committed and proven in a court of law. Fundamental questions concerning due process, personal liberty, and the presumption of innocence are brought up by this distinction. However, preventive detention is a topic of intense legal scrutiny and discussion because the Indian legal system permits it under certain circumstances. Prevention of Detention Law has been influenced by seminal decisions such as A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, ManekaGandhiv. Union of India, and A.K. Roy v. Union of India. The paper advocates for a more rights-based approach and proposes strong legislative and judicial safeguards to prevent the abuse of preventive detention authority.

Constitutional Framework

Article 22 of the Indian Constitution specifically protects the rights of those detained pursuant to preventive detention laws.Clauses 3–7 only apply to preventive detention, despite the fact that Articles 22(1) and 22(2) provide protections for those detained under regular laws.Clause (3) exempts preventive detainees from the protections provided by clauses (1) and (2).Clause (4) authorizes such detention for up to three months without seeking the advice of a High Court Advisory Board. According to clause (5), detainees must be informed of the reasons for their detention and given the opportunity to object.Clause(6), on the other hand, allows the state to conceal information deemed to be contrary to the public interest, while Clause (7) allows Parliament to specify the maximum length of incarceration as well as procedural details. Although Article 21 does not cover preventive detention, the framers included procedural safeguard to protect against capricious abuse. During the Constituent Assembly Debates,Dr.B. R. Ambedkar recognized preventive detention as “a necessary evil” requiring careful constitutional regulation.

Preventive Detention Legislation in India

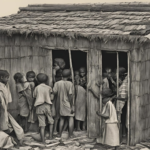

The Preventive Detention Act of 1950 was the first of several preventive detention laws passed by India over the years. This Act, passed under Article 22(7), allowed for detention without trial for up to one year. It was repeatedly extended untilit expired in 1969, despite its initial intention to be temporary.This was succeeded by the stricter Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) of 1971. During the 1975–1977 Emergency, MISA was widely used to imprison activists, journalists, and political opponents. After democratic governance was restored in 1978, MISA was repealed due to widespread abuse of legal authority.

Judicial Interpretations and Safeguards

The Supreme Court has played an important role in establishing individual rights and interpreting preventive detention laws. A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950) was the first major case in which the Court upheld the Preventive Detention Act’s constitutionality. According to the majority opinion, Article 22’s procedural safeguards were adequate,andArticles21and22 were distinct. Because of this interpretation, preventive detention was allowed to continue with minimal judicial oversight.

However,inManekaGandhiv.Union of India (1978),the Court rejected Gopalan’srestrictive interpretation, holding that any law denying someone’s freedom must be fair, reasonable, and just.This decision strengthened judicial oversight the scope of Article 21.

The Court upheld the constitutionality of the NSAin A.K. Roy v. Union of India (1982), but it also emphasized the importance of procedural safeguards. It stated unequivocally that Article 21 applies to preventive detention as well, and that the detainee must be given sufficient information to effectively represent themselves.

In Mohd.Yousuf Ratherv.State of Jammu and Kashmir (1979), the Court upheld the principle that detainees must be fully informed of the reasons for their detention by invalidating a detention order because it was vague. Similarly, in Alijav v. District Magistrate, Dhanbad(1985), the Court stated that the detaining authority’s subjective satisfaction must be supported by concrete and objective evidence. The serulings demonstrate the judiciary’s attempt to strike a balance between individual rights and state interests by ensuring that laws governing preventive detention meet constitutional requirements.

Contemporary Issues and Case Studies

In light of public protests and political detentions, preventive detention has attracted renewed interest.A number of political figures, including former chief ministers, were imprisoned under the Public Safety Act (PSA), a state-level preventive detention law, after Article 370 was repealed in Jammu and Kashmir in 2019.These detentions, which were defended as necessary to keep the peace, were criticized for being capricious and undemocratic.

The preventive detention of a number of demonstrators and activists during the 2019–2020 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests drew criticism from legal scholars and civil rights organizations. Preventive detention is frequently used to suppress political opposition and dissent, though courts have occasionally stepped in to free detainees.

Similar trends were seen during the farmers’ demonstrations and other large-scale mobilizations, when laws pertaining to preventive detention were used in advanceto stop meetings or protests.

Conclusion

In India, preventive detention has a controversial place in the legal and constitutional system.

Public order and national security are legitimate goals of the state, but they shouldn’t come at the expense of constitutional rights and fundamental freedoms. In order to maintain procedural justice and enforce checks, judicial decisions have been essential; however, more must be done to stop the abuse of these extraordinary powers.

Author Name–Ritika Sharma, Lords University, Alwar