Introduction

In recent years, India has been seeing a very intense debate about just whether or not criminal laws should be women-centric or become gender-neutral frameworks. In one hand, cases such as the tragic death of Atul Subhash highlight how Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, originally enacted for protecting women from cruelty by husbands as well as in-laws, is sometimes misused; this then leads to catastrophic outcomes for men along with their families. In addition, incidents like the Sonam Raj “honeymoon murder case” of Meghalaya remind us women can perpetrate grave crimes too. Therefore, the long-held perception of women as only victims inside the justice system is challenged.

This blog addresses that problem since it targets Section 498A as the centre of the gender-neutrality discussion, and it explains why India cannot now discard protections focused on women despite their abuse. As we navigate these difficult conversations, one truth remains clear that justice should never come at the cost of another’s suffering.

Public Perception and Debates around Gender-Neutral Laws

The MRA, or men’s rights activism in India, has transformed into an important social movement and is doing a lot using social media to promote legislative lobby support and protest in the street, raising public opinion on their sufferings, at least the misuse of Section 498A against men. [1]Although this movement started out as scattered endeavours in the early 1990s, especially given cases such as Atul Subhash’s tragic death have become rallying points, strengthening the perception that protective laws can sometimes be weaponized against men. Similarly, the rise of cases where women are the aggressors, such as the Sonam Raj “honeymoon murder” case, has added fuel to the demand for gender-neutral laws.

However, much of the discourse generated by MRAs tends to focus on criticizing feminism—using arguments like “men go through this too!”—rather than proposing constructive solutions. This is therefore reflected in the outrage of the public and, consequently, a balanced approach needs to be formulated where the voiced grievances of both sexes are considered, without compromising on the protections of vulnerable groups.

Raising Voice for Men’s Rights in India

Women’s rights issues are given high priority since they are considered, for the most part, as victims in a majority of situations. This focus, however, tends to push the suffering of men, who may also face numerous injustices because of the arbitrary or injudicious application of protective laws to the backburner. Under Sections 375 and 376 of the IPC, only a “woman” can be recognized as a victim of rape, and only a man can be considered the perpetrator. Even the newly proposed Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS) fails to acknowledge male victims of rape. Notably, the Justice Verma Committee had recommended making rape laws gender-neutral, yet this suggestion remains unimplemented. [2]

Coming to the main highlight ofthis blog, it revolves around Section 498A of the IPC, which defines “cruelty” (now replaced by Sections 85 and 86 of the BNS). In recent years, there have been growing concerns as more cases have surfaced where this law, intended to safeguard vulnerable women, has been misused, transforming a shield into a weapon also affecting innocent lives consequently.

Section 498A IPC reads as: “Whoever, being the husband or the relative of the husband of a woman, subjects such woman to cruelty shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine.”[3]

In the case of Sushil Kumar Sharma v Union of India[4]in 2005, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of Section 498A IPC, affirming its critical role in protecting women from cruelty and harassment and recognizing concerns over its potential misuse. However, the law should never be an instrument to satisfy some clandestine agenda or personal revenge since this defeats its actual purpose and the very notion of justice that it is attempting to preserve. In this judgment, rendered about two decades ago, the Court cautioned that misuse of Section 498A IPC could unleash a “new legal terrorism”.[5]

The judiciary has gone a step further in the case of Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar[6]by commanding the state governments to ensure that arrests under Section 498A are not done mechanically. Police officers were, therefore, cautioned to think through the necessity of arrest before detaining an individual and avoid further unwarranted detention.

These changing legal landscapes may be reflections of an unfolding legal scenario and considering all standpoints, this underlying structure remains tilted in the women’s direction due to its nature in an otherwise patriarchal society. As reflected in Atul Subhash’s tragic situation, safeguards that avoid misuse do need to take into account protection for those endangered by systemic cruelty.

Why India Still Needs Women-Centric Laws: A Fight Far from Over

Although there exist a myriad number of laws on the books that are specifically woman-oriented, including the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, anti-dowry laws, and stern rape laws, the facts and figures beg to differ. That raises a critical question: Why, in the 21st century, do newly enacted criminal laws favour women? The answer lies in the deep-seated struggles that persist, systemic challenges women face. Despite years of progress in women’s empowerment, India remains largely a male-dominated country. This persistence suggests an intricate relationship between the nation’s legal framework and the prevailing societal mindset.

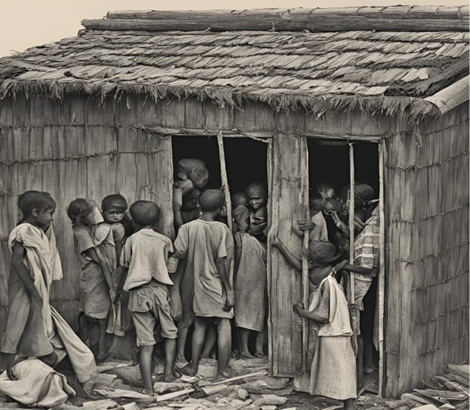

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a ghastly trend, where newlywed women were being set on fire in their marital homes, their deaths staged as kitchen accidents when they were unable to bring enough dowry. The haunting echoes of burning brides, the silent cries behind closed doors, and the bruises hidden beneath saree folds, these are not just leftovers of a dark past but are a reality that continues to plague India. It was during that period of horror that Section 498A was created to protect the principal facet of this very case, this is, thus, a landmark legal support instrument for the hapless lady mired in torture marriages. Enacted in 1983, Section 498A criminalizes cruelty by husbands and in-laws, offering women a chance to seek justice before it is too late.

Statistically at the national level, in 2020, the total cognizable CAW (Crime Against Women) was 371,503, whereas, in 2022, this number increased to 445,256. Of the total cognizable CAW in the year 2020, the highest proportion (30%) was attributed to individuals close to the victim, including her husband or his relatives[7]. Over 4,45,256 cases of crimes against women were reported, averaging 51 cases every hour. [8]All these reports are based on NCRB (2020-22) and the most common crimes? Cruelty by husbands and in-laws, domestic violence, sexual assault, and dowry-related harassment.

The recent outcry over alleged misuse of women-centric laws cannot erase the harrowing truth that these laws were born out of centuries of suffering and they remain essential even today. In a society where women are still unsafe in their own homes, where marital rape remains unrecognized, and where victims of abuse are silenced under societal pressure, how can we afford to weaken these protections?

Conclusion

The debate over gender-neutral laws is complex as well as deeply emotional because cases have shaped it where men have suffered under false accusations in addition to accounts of women facing persistent cruelty within their homes. Section 498A stands amid the center of this debate, commended as a lifeline for women in distress. The section is also criticized as a tool prone to misuse. It is important to have an acknowledgement of both realities Misuse is real, but does it erase the systemic violence, dowry deaths, and domestic abuse that still plague Indian households?

It is necessary that the Supreme Court’s Arnesh Kumar guidelines are strictly followed by law enforcement so that such women-centric laws protect those who are in actual need and do not let it be misused. Police officers should be brought to book if they do not approach cases with fairness and impartiality, and every individual should be treated justly. At the same time, laws need to be amended with strict penalties for false complaints so that no one suffers from malicious complaints.

It is equally important that men, too, have access to helplines and support systems, offering legal aid and emotional support to those wrongfully accused. Finally, by having an independent review committee to review regularly how the women-centric laws are being applied, we will be able to strike a better balance between honouring the intent behind these laws and safeguarding against their misuse.

The answer is not to take away protections but it is instead to better implement them so as to ensure justice is fully served for all people, without then tipping the scales too far in either direction. In the end, this is about ensuring fairness, dignity, also the right to live without fear for everyone. Regardless of gender, this issue is not about men versus women.

[1]Harleen Kaur, Meenakshi Rani Agrawal and Surbhi Agrawal, ‘Men’s Rights in India – Gender Biased Laws’ (2023) 12(4) International Journal of Science and Research 1006 https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v12i4/SR22114163536.pdf accessed 12 September 2025.

[2] PRS Legislative Research, Justice Verma Committee Report Summary (2013) https://prsindia.org/policy/report-summaries/justice-verma-committee-report-summary accessed 12 September 2025.

[3] Indian Penal Code 1860, s 498A.

[4] Sushil Kumar Sharma v. Union of India, (2005) 6 SCC 281.

[5] Debby Jain, ‘S.498A IPC: How Supreme Court Raised Concerns About Misuse Of Anti-Dowry & Cruelty Laws Over Years’ LiveLaw (15 December 2024) https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-take-on-misuse-of-section-498a-ipc-cruelty-harassment-over-implication-of-husband-family-278393 accessed 13 September 2025.

[6] Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (2014) 8 SCC 273.

[7]B S Pooja, Vasudeva Guddattu and K Aruna Rao, ‘Crime against women in India: district-level risk estimation using the small area estimation approach’ (2024) Frontiers in Public Health 12:1362406 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11288248/ accessed 13 September 2025.

[8]Sonali Verma, ‘India records 51 cases of crime against women every hour; over 4.4 lakh cases in 2022: NCRB report’ Times of India (3 April 2024) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-records-51-cases-of-crime-against-women-every-hour-over-4-4-lakh-cases-in-2022-ncrb-report/articleshow/105731269.cms accessed 13 September 2025.

Author Name- Vaishnavi Gupta, Second-Year, B.Sc. LL.B. Student, National Law Institute University (NLIU), Bhopal